|

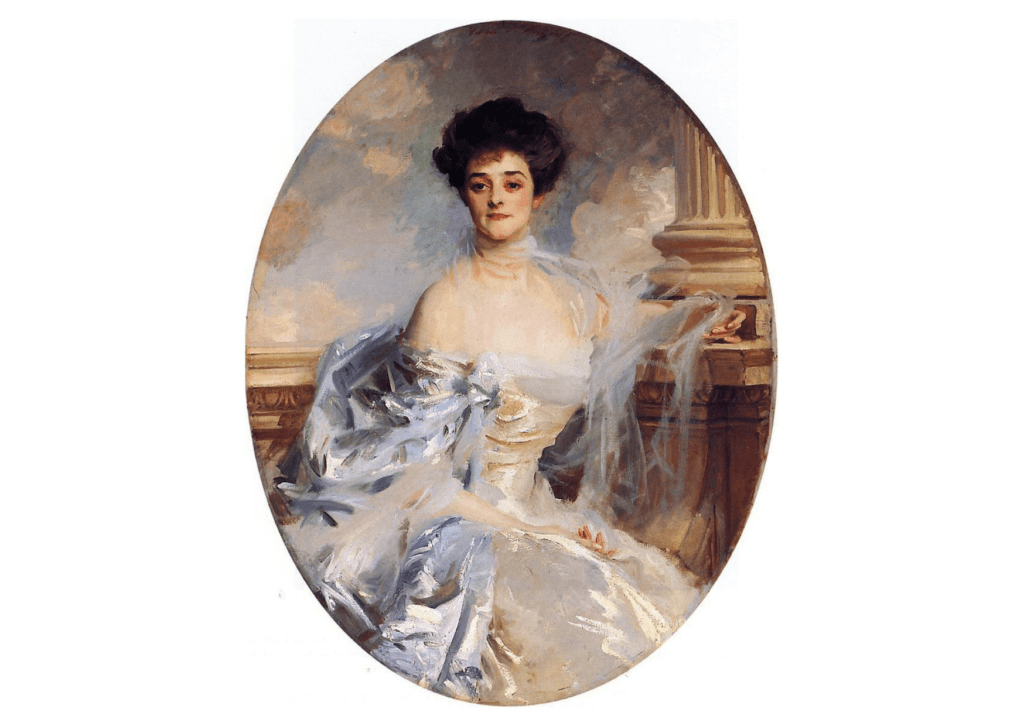

In the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Texas, hangs an oval-shaped oil painting of a woman in a billowing, silvery-blue dress. She gazes directly out of the frame, one hand resting on a column, the other poised in her lap. Painted by John Singer Sargent, the most celebrated society portraitist of the Edwardian era, the portrait shows Adele Capell at the height of her status: elegant, composed and unmistakably at home in high society.

2RC91XW The Countess of Essex 1907 by John Singer Sargent

But as with many great portraits, the surface conceals a far more complex story – one that leads, eventually, to Eastnor Castle. Adele Capell, Countess of Essex, was not born into the British aristocracy. She was one of the so-called “dollar princesses” – American heiresses who, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, crossed the Atlantic to trade immense wealth for European titles. But in Adele’s case, the “dollar” part wasn’t quite accurate. Her father, David Beach Grant, had made his fortune manufacturing locomotives, but the business was collapsing after a disastrous cancelled order. And so at the start of the 1880s, her mother gathered her daughters and headed for Europe. Adele quickly realised that her fortune was a fantasy and she needed to do something – and fast. Marriage, preferably to an aristocrat, would give the family the anchorage and status her father had sabotaged. And at the time, Americans were fashionable in British courts; their money, sophistication and candid confidence made them popular. The Prince of Wales liked them as they ‘could tell a good story and were born card players’, and nobles were eager to marry into new money and secure one of these glamorous Americans as a wife. Novelists like Edith Wharton and Henry James (who would later become part of Adele’s social circle) even immortalised this shift in works like The Buccaneers and The Europeans. So, after spending a year at The Sorbonne in Paris, where she immersed herself in learning the French art of effortless beauty, Adele arrived in England. She was an instant hit. Paris had taught her that appearances could be as persuasive as truth – that admiration didn’t always depend on reality, only on perception. And her extensive time in France, exquisite taste in everything from art to fashion, and pure, unmarred beauty all painted the picture of a perfect, pond-crossing princess. Next on her list: finding a suitable husband. She was first engaged to Lord Cairns, but this ended in scandal after he revealed himself to be little more than a cad who was more interested in her money than her mind – culminating in him insisting she repay him for the lavish gifts he had given her. Unwilling to foot the bill, and affronted by this degrading demand, Adele broke off the match.

However, all was not lost. Soon after, she married the 7th Earl of Essex, becoming Countess and moving to his estate, Cassiobury Park near Watford. As an engagement gift, her husband-to-be gave her a Cartier diamond tiara to show that, unlike her previous match, he wasn’t all about the money; it was Adele he liked. (The tiara, incidentally, would go on to be worn by Clementine Churchill and, more recently, Rihanna on the cover of W Magazine.) Adele had become the Countess of Essex; the powerful, purposeful figure painted by Sargent in 1906. She was celebrated as one of the “Lovely Five” – a group of duchesses and countesses admired for their beauty – and became known for her style, taste and intellect. She had two daughters, hosted Henry James, Arthur Sullivan and her great friend Edith Wharton, and her social circle revolved around “The Souls”, a group of literary-minded aristocrats who preferred salons to shooting parties. She may even have been one of the first women to drive a motor car. Yet despite appearances – the portrait, the title, the grand house – Adele was under constant pressure to keep up. As it turned out, her husband’s financial situation was not good. Cassiobury Park was mortgaged, not owned outright. She couldn’t afford the couture gowns her peers wore, so had London dressmakers copy Parisian designs – paying for them, rumour has it, with poker winnings. She habitually posted books or photographs of herself to powerful men she wanted to be associated with, forcing them to send a reply – the kind of social proof she needed to reinforce her status. In 1920, it all came crashing down. Her husband had died a few years previously in a carriage accident, and she ended up selling Cassiobury Park and all its contents in a public sale. Two years later, she died unexpectedly at her new home in Brook Street, Mayfair. Family speculation lingered around both her and her late husband’s deaths – whispers of misfortune, or perhaps something darker. Either way, the world Adele had worked so hard to remain part of had finally slipped from view. Next month, Kenwood House in London opens a new exhibition of Sargent’s portraits of American heiresses – including many of Adele’s contemporaries. These paintings depict powerful women, often misunderstood, asserting their place in a society that never quite saw them as belonging. Adele’s portrait isn’t in the show. But perhaps that’s fitting. Her story – private, precarious and endlessly resourceful – still lives on, not just in paint and canvas, but in places like Eastnor Castle, which has its own legacy, tied to both history and family. If you haven’t yet guessed the connection, Adele was the great-great-grandmother of Eastnor’s current custodian, Imogen Hervey-Bathurst. What’s more, two of the paintings from her original Cassiobury estate now hang on the castle walls, having found their way back to the family after generations apart. They are a subtle reminder of a woman who understood that appearances weren’t everything – but sometimes, they were all you had. Heiress: Sargent’s American Portraits opens at Kenwood House on 16 May; english-heritage.org.uk |

30 Apr 2025

From Cassiobury to Eastnor: the remarkable life of Adele Capell

She was Sargent’s muse and a society beauty, but the Countess of Essex’s story was far from a fairytale. A century on, her legacy continues at Eastnor Castle